photo by Ann Aurbach

Fairground is a neighborhood in north St. Louis with namesake ties to the once renowned St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association Fair, which occurred for nearly a half century in adjacent Fairground Park. Like many neighborhoods nearby it, Fairground is a community full of history, both painful and proud.

photo by Sue Rakers

photo by Jan Markham

photo by Kate Cawvey

photo by Diana Linsley

Far from the city center of St. Louis, the area that would become Fairground was little more than windswept pastures prior to 1856. The land itself, derived from the former common fields of the city, was then owned by some of the city’s wealthiest family names and was merely the location for a few sprawling ranches with the occasional, intermittent farm house. But, in this year, something changed.

As early as the 1820’s, there was interest in the possibility of establishing an annual agricultural fair for the region, which conceptually languished until gaining momentum and support in the late 1840’s. By the 1850’s, the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association, a relative upstart, had amassed $50,000 from investors to purchase a sizable, 50 acres from John O’Fallon, near the present day intersection of Grand and Natural Bridge. The rapid construction of a smattering of buildings, outbuildings and fountains followed, such that by the Fall of 1856, the first “Fair” opened to the public to universal acclaim.

Over the fifty years that followed, the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association Fair became known throughout the world, and hosted an inimitable cache of attractions that included the Buffalo Bill traveling show, horse racing and its posh “Jockey Club”, visits from three U.S. Presidents, hot air balloon ascents, the Zoological Gardens (our city’s first), floral and fine arts halls, a visit from the Prince of Wales, and even the first organized game of baseball played in St. Louis.

Unfortunately, the decline of the Fair was nearly as swift as its startup. Despite having survived the Fair’s postponement and the Fairground’s conversion to use as a hospital and military barracks (Benton Barracks) during the Civil War, the annual event lost its significance in the face of several circumstances. These included changes to the laws regarding gambling (horse racing was a staple draw for organizers), competition from other newer attractions closer to Downtown, and the public’s general declining interest in the annual “big event” (perhaps preoccupation with the city’s bid for the World’s Fair had something to do with it). Nonetheless, the last St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association Fair occurred in 1902, and by the time of its opening as a city park in 1908, the site had been cleared of most of its buildings and structures. Notably, the “Bear Pit”, a leftover enclosure from the former zoo, was spared and integrated into George Kessler’s design for the Park.

photo by Liz McCarthy

photo by Patrick Collins

photo by Theresa Harter

photo by Jane DiCampo

Historical illustrations of the Fairgrounds area during the height of the Agricultural Fair illustrate two things. The first is that considerable development was occurring in the land south of and east of the Park, and the second is that a small agrarian community with at least one industrial complex existed north of the Park. These illustrations suggest two distinct characters–one for north of the Park with generally smaller residences and roadways that meander along old trade routes and former topographical features, and one for east of it with larger, more mansion-like residences arranged on a tighter grid–both carry over into what exists there today.

Plate 81 from Pictorial St. Louis, 1875; Richard Compton & Camille Dry; Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. (Grand is on the bottom in this map)

St. Louis Fair Grounds, Containing Eighty-three acres of land, 1874;Julius S. Walsh, Presdt., G.O. Kalb, Secty. Lithograph by St. Louis Democrat Lith. and Print. Co. after Camille N. Dry; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society NS 21713 (Natural Bridge is on the bottom in this map)

This development, likely dating back to at least the 1850’s, is notable given that the Fairgrounds were several miles from Downtown, on the very outskirts of town, during this time. Certainly, this makes Fairground among the older neighborhoods in its immediate vicinity (with the exception of Hyde Park).

photo by Joe Harrison

photo by Maureen Minich

photo by Joe Rakers

photo by Yvonne Suess

During the conversion of the former Fairgrounds into Fairground Park, the site’s former amphitheater, a circular structure that was once the world’s largest of its kind, was razed, and on top of the footprint, the world’s largest public swimming pool was constructed. This pool, a favorite summer attraction for tens of thousands of St. Louisans, was also the location for the most significant race riot in the history of St. Louis.

In 1949, desegregation of the city’s outdoor pools was finally declared, so when the pool in Fairground Park opened in June, the large crowd of revelers included a small number of African American men and boys. Throughout the day, a mob of enraged Whites grew outside the fence, until the police were dispatched to escort the Black swimmers safely from the pool area (there are contradictory reports about how “safe” that passage actually was). Nonetheless, violence erupted nearby, with bricks, knives, fists, and defamatory words wielded against hapless Black men, women and children. Overnight, the melee spread throughout the city, especially with regard to public transportation, and more than 150 policemen (official reports range from 150 to 400) were needed to quell the onslaught. The next morning, St. Louis Mayor Joseph Darst, reversed the procedure of integration, and the pools once again became segregated for an additional year, when Federal Law intervened to abolish the practice (a precursor to the eventual Supreme Court ruling against segregated schools). For days after the event, racial tensions boiled over, as expressed in fisticuffs. Newspapers from St. Louis to publications as large as Time Magazine documented the scene (against the city’s preference to downplay the events), mostly with heartbreaking images of young Black men in torn clothing and covered in blood, on the ground and surrounded by their White assailants. 60 years later, one of the Black youths who had been at the pool that day and attacked on his way out expressed it this way, “I thought all White people hated us.”

The events of June 21, 1949 had an undeniable impact on St. Louis City as a whole. It occurred on the essential cusp of “White Flight” of city residents to the suburbs, and during a period of Black migration and population growth for the city. The practices of redlining and restrictive deed covenants were still in place, though they were becoming challenged throughout the city, most especially in north St. Louis. The Civil Rights Movement was burgeoning. Despite all of the change inherent to the time period, both locally and nationally, Whites and Blacks in St. Louis were still mostly isolated from one another, by both personal decision and institutional design (something that remains a problem).

However, in the years following, as the neighborhood of Fairground transitioned from predominantly White to predominantly Black, there are some outliers to the abundant accounts of racial friction. Like the story behind the former Red Bones Den, an iconic lounge that started operations on the corner of Kossuth and Prairie in the early 1970’s. We invite you to click the link to read more, but essentially, a White building owner gave a young Black man with extraordinary determination the keys to her property for only $12 down. Definitely, this does not negate the dramatic need for institutional change or erase racial injustice, but it does show that humanity exists even in situations that may, on the surface, appear to lack it.

photo by Jason Gray

photo by Kate Cawvey

photo by Mike Matney

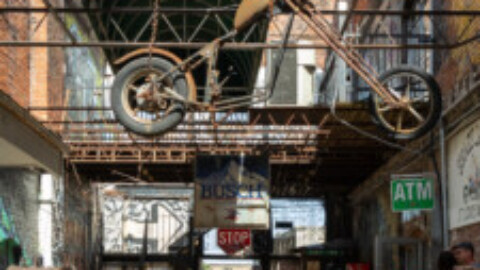

Today, Fairground is a complex neighborhood, a description that, though vague, is undeniably accurate. In previous censuses, the neighborhood has struggled in largely the same ways as the city of St. Louis as a whole (a decreasing population and an increase in building vacancy, among other factors, like controlling crime). That said, the neighborhood does show signs of recovery–certainly, it is positioned well for that alongside the city’s fourth largest park. There is revitalization in commercial corridors throughout the neighborhood, which surprisingly, has many, and there are plenty of storefronts that are already open for business.

Take, for instance, the Playground Bar and Grill on Kossuth, whose proprietor we were able to meet on our visit. The last time that we photographed Fairground Park, the building now hosting this business was vacant and deteriorated. Now, it has been beautifully restored, and will be a great spot for us to visit as a Group on our next return. Playground is only one example, but is indicative of others around the neighborhood; businesses that don’t receive much fanfare across the city when they open, but are great examples of a neighborhood doing what’s necessary to lift itself up, through hard times and beyond.

photo by Jane DiCampo

photo by Gerry Clarke

photo by Diane Sieckmann

photo by Joe Rakers

Map available here.