photograph by Anne Warfield

Historic Fairground Park was purchased by the city in 1908 from a private entity which had hosted an annual agricultural fair on the land since the mid-1800’s. The Agricultural and Mechanical Fair, as it was known, drew huge crowds from all over the country, but was suspended during planning for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 , and never reinstated. The Park is notable for several features, namely as the site of the city’s first zoo (a facade for the bear pits is still visible) and first municipal pool. Unfortunately, Fairground Park was also ground zero for the race riot of 1949 that stemmed from the desegregation of public pools. Racial tension is still a point of contention for the park as evidenced in recent news events. Still, Fairground Park is a beautiful natural respite on the city’s north side that offers many opportunities for recreation.

photograph by Scott Jackson

photograph by Amanda Miller

photograph by Scott Jackson

photograph by Michelle Williams

A year before the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association staged its first grand exposition on the fifty acre site that would grow to become the present Park, the land expanding northwest from Grand Avenue and Natural Bridge Road was little more than a grassy pasture owned by John O’Fallon (the nephew of explorer William Clark, who had his farmstead just to the north, at present-day O’Fallon Park). During this time, the Association had since garnered considerable support from local residents in order to purchase the land using donated funds, for $50,000. The Fall of 1856 saw the first fair at “The Fairgrounds” open to wide acclaim. Surrounded by a nine-foot tall fence, the St. Louis Fairgrounds featured a plethora of fountains, several buildings and outbuildings, and the world’s largest amphitheater at the time (a circular, coliseum-like structure with a 36,000 person capacity).

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Scott Jackson

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Anne Warfield

Over the fifty years that followed, the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association Fair became known throughout the world and hosted an inimitable cache of attractions that included the Buffalo Bill traveling show, horse racing and its posh “Jockey Club”, visits from three U.S. Presidents, hot air balloon ascents, the Zoological Gardens (our city’s first), floral and fine arts halls, a visit from the Prince of Wales, and even the first regular game of baseball played in St. Louis. During the Civil War, the annual fairs were postponed and the grounds turned over to 20,000 troops who established a military barracks and wartime hospital.

After the war, the business of organizing the annual fairs returned to normal (attendance even peaked during the 1870’s). In 1874, the Association approved opening the Fairgrounds to the public during times of the year when events were not scheduled. Given all of this early success, it is almost inconceivable to imagine the decline that would eventually follow.

photograph by Scott Jackson

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Michelle Williams

A number of factors contributed to the abolition of the annual fairs in 1902. Chief among them was the fact that the city was preparing for an even grander spectacle to unfold in Forest Park in 1904. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition (locally dubbed, the “St. Louis World’s Fair”) was to be the second largest world’s fair in history, and ushered in an international audience of more than 19 million people. When the crowds cleared from Forest Park, the yearly event staged by the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association was all but forgotten. Also aiding to this quick demise, was the establishment of the annual Veiled Prophet Parade which drew away additional attention, and the election of a Missouri Governor who opposed gambling (a crushing blow to the Jockey Club). From 1902 to 1908, the St. Louis Fairgrounds sat vacant, awaiting its new use as the fourth largest public park in the city.

photograph by Ann Aurbach

photograph by Amanda Miller

In 1908, the city brokered a deal to acquire the now 129-acre park. Renamed Fairground Park, the land was dedicated to the people of St. Louis in October of 1908, devoid of its characteristic structures (the city razed the Jockey Club, and all of the other buildings except for the amphitheater which was destroyed in 1911, and the bear pit facade). Nonetheless, the Park served its surrounding neighborhood well through the years, offering a front yard for Beaumont High School and a site for the city’s first public pool. Built on the spot of the amphitheater, the pool was acknowledged, like the building before it, as the largest such structure in the world. Originally a source of pride for the community, the municipal pool at Fairground Park took on a sinister role in 1949, when it became the epicenter for a race riot that engulfed the city. Earlier that year, desegregation of the city’s outdoor pools was decided, and when the pool in Fairground Park opened in June, the large crowd of revelers included a small number of African American men and boys. Throughout the day, a crowd of enraged whites grew outside the fence, until the police were dispatched to escort the black swimmers safely back to their residences. Nonetheless, violence erupted nearby, with bricks, knives, fists, and defamatory words wielded against hapless black men, women and children. Overnight, the melee spread throughout the city, especially with regard to public transportation, and more than 150 policemen were needed to quell the onslaught. The next morning, St. Louis Mayor, Joseph Darst, reversed the process of integration, and the pools once again became segregated for an additional year, until Federal Law intervened to eliminate the practice.

photograph by Scott Jackson

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Scott Jackson

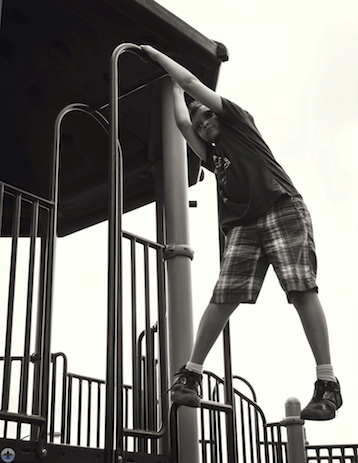

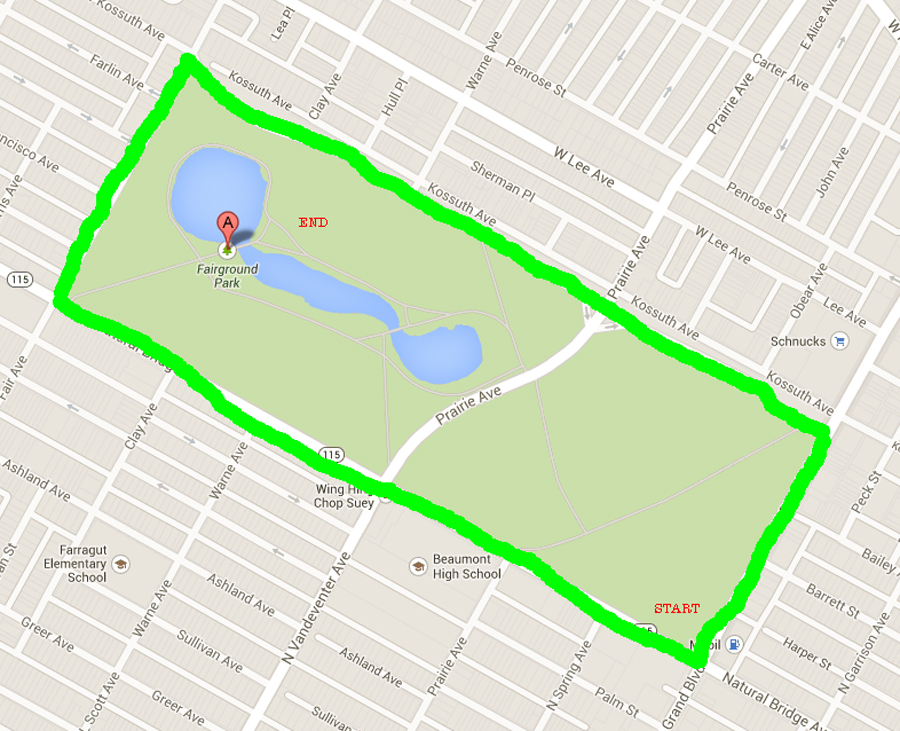

In the decades following 1949, the demographics of the city changed drastically. Faced with significant population loss and economic decline, the neighborhoods surrounding Fairgrounds Park (O’Fallon, Fairground, Greater Ville, and JeffVanderLou) became increasingly neglected. Today, this neglect is easily visible in the Park, taking the form of deteriorated playgrounds, unkempt ballfields, and shuttered public facilities (one portable toilet services the entire Park, and the associated hand-washing station was out of supplies on our visit; this is entirely unacceptable!). A nearby resident, who was in the Park with his son that day, summarized the present conditions well, “The neighborhoods around here are full of poor people, and poor people aren’t considered as important.” However, the city’s presence was felt. Beginning on Memorial Day of 2014, the city barricaded Fairground Park to through-traffic, and set up police stations around the Park to monitor who was entering. This effort was made as the result of the Park having had the highest incidence of violent crimes anywhere in the city up until that point of the year. On the day that we visited, the police presence was palpable, and increased as the day went on. While the effect of these barricades may be an immediate reduction in crime, they also have the effect of reducing the enjoyment of the Park for local residents. After all, how many of you would be willing to put up with vehicle inspections, id checks, insurance verifications, etc. just so that you could enter into Forest Park? Not many, I suspect. It is true that something needs to be done to make the Park safer and to curb endemic crime, but I don’t know that a veritable “police state” is the right answer. Possibly, a better start would be to open up some of the public restrooms, fix the dangerous holes in the kids’ slides, add organized sports programs, and do a few other small steps that would encourage local residents to enjoy the Park in ways that do not elicit crime. After all, as the man we met told us, “People are people; they enjoy the same things, no matter where you go, rich or poor.”

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Anne Warfield

photograph by Ann Aurbach

After the Flood, we took advantage of the beautiful, natural setting, and staged our first PFSTL picnic. Hotdogs, veggie dogs, chips, potato salad, soda and/or Lime-a-Ritas were enjoyed by all.

(Author’s note: None of the above is meant to be a rant against the Metropolitan Police Department. The work that they do is important, brave work, and three generations of my own family have served loyally as St. Louis City officers. Much rather, I view the current actions in Fairground Park as pitting the police against local residents, some of whom may already possess a somewhat negative or suspicious view of police work. This makes the job cops do more dangerous, and does not necessarily eliminate crimes from occurring; much rather, it forces crime to move to other parts of the city.)

[…] has visited all of the four largest city parks, Forest Park, Tower Grove Park, Carondelet Park and Fairground Park. Without a doubt, each green space is punctuated with an individual character that is informed by […]