photograph by Michelle Williams

Clayton, the administrative and economic center of St. Louis County, shares a relationship with St. Louis that is both symbiotic and affronting. In 1876, residents of the city grew tired of seeing their tax contributions distributed to what was then a small population spread across a vast area; reasoning that the city would be unlikely to ever grow beyond its current border, legislation was drafted that would formally separate the city, and its 300,000+ residents, from the county, with its measly 20,000+. If the situation had remained forever as it was then, this move would have made sense, especially since the much larger city required exponentially more funds to extend services to its residents. However, not long after the split was made final (a move known as The Great Divorce), St. Louis was already pressing against its boundaries, which did not prevent growth from occurring outside of them, and in fact, exacerbated new development within the city limits. In the long history of St. Louis, no decision had more deleterious an effect on the stability of the municipality than deciding to form an independent city, seceded from St. Louis County.

Still, one might feel compelled to ask, were there any benefits to the Divorce? The answer is yes, for Clayton.

photograph by Jeni Kulka

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Jessica Rugh Winter

photograph by Ann Aurbach

In 1876, St. Louis was a bustling place with much reason for optimism about its future. After all, the city had survived the Civil War virtually unscathed, was recognized as the United States’ fourth largest city in the 1870 census, experienced significant transportation development and industrial growth, and there was even a plan to move the District of Columbia to Mound City. What’s more, the city had recently installed the largest public park in the country at the time, with beautiful wide boulevards (proposed) and a rail line connecting it to Downtown. Up until this point, most population expansion in the city had stretched north and south of Downtown along the Mississippi River, but Forest Park was to be the encouraging factor for this expansion to begin moving west. Indeed, this migratory plan did work, resulting in wonderful urban neighborhoods like the Central West End, DeBaliviere Place, and more. Unfortunately, once the population reached the city’s borders, there was no way to curb the momentum.

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Jeni Kulka

photograph by Jason Gray

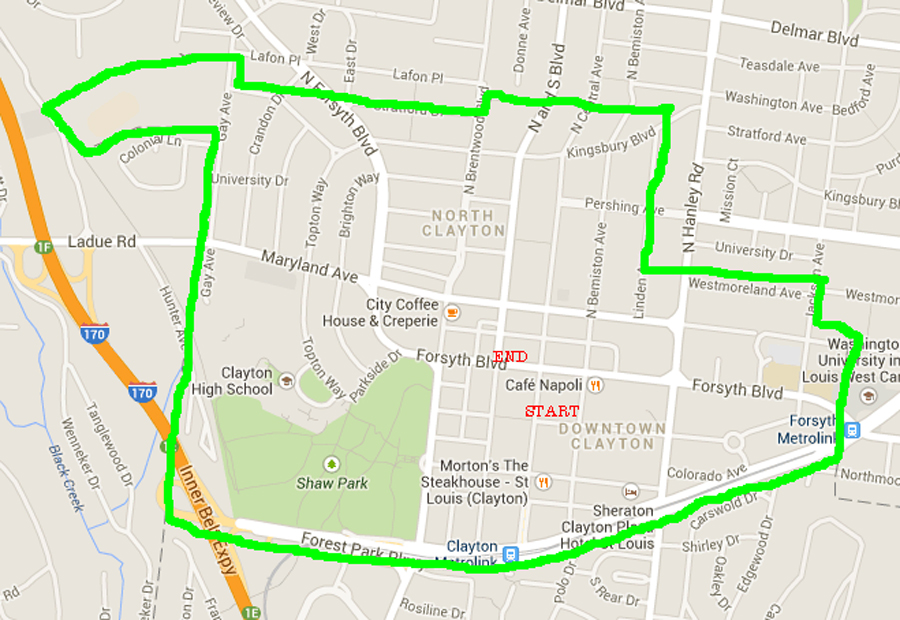

Though St. Louis County had lost much financially in the initial separation from St. Louis city it was determined to prosper. In the same year as The Great Divorce, the county formed a commission to oversee the establishment of a new county seat (one to replace St. Louis). Eventually, they approved a proposal put forward by Martin Hanley and Ralph Clayton, who together had agreed to donate 104 acres to a new municipality. The location could not have been better. As previously mentioned, St. Louis City had already created momentum for westward development, and once the transportation infrastructure was in place to connect Downtown to the Central West End and Forest Park, it was inconsequential to extend it a bit further into Clayton (so named because Ralph Clayton had donated more of the principal land). Additionally, the Missouri-Pacific Railroad had a line traversing through the County, just to Clayton’s south. So it was that Clayton came to be, and so it was over time that the more St. Louis City lost (population, industry, investment, etc.), the more Clayton seemed to gain.

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Ann Aurbach

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Jessica Rugh Winter

photograph by Jason Gray

After World War II, St. Louis City, like most eastern metropolises, experienced significant population declines in its urban core. However, unlike some other cities, St. Louis was unable to compensate for the population shift by expanding its borders. Locally, this resulted in a population loss of over 500,000 people. During the same time, St. Louis County’s population grew, from 30,000+ in 1940 to 1,000,000+ in 2000. This explosion of new residents resulted in one of the most complete stocks of modernist buildings being located in downtown Clayton. Truly, an aerial view of the region makes it seem as if St. Louis has two downtowns, one designed to benefit from river transportation and the other situated to capitalize on a vastly dispersed economic area.

photograph by Ann Aurbach

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Ann Aurbach

Over the years, there have been many attempts to reunite both city and county, but each have been rejected by voters. Today, as St. Louis celebrates its 250th anniversary of its founding, the topic is fresh again. Unlike previously, when either the city or county stood to lose something from reunification, both now seem poised to benefit. Though the city is no where near its peak era, it has experienced lots of regrowth and new investment (especially in technology and the arts). Meanwhile, St. Louis County has experienced its first negative population trend over a ten year period (2000-2010) since it lost St. Louis. Could it finally be that the best solution for both parties is to reunite after all of these years? If so, what will the in-laws think?

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Jeni Kulka

photograph by Jason Gray

Our endpoint for the night was Barrister’s, which is an excellent pub with friendly service, delicious fish and chips, and a nice beer selection.

photograph by Jason Gray