photograph by Dan Henrichs Photography, St. Louis

The story of water distribution in St. Louis is a marvelous tale of engineering might combined with a fast-rising city’s Victorian sensibilities. The first water delivery operation was a privately held company that went into business amid the first major influx of German and Irish immigrants in the 1830’s. However, by the end of that decade, the city had become sole owner of its waterworks. It had also inherited a major health problem with subsequent outbreaks of Cholera, which were to become the worst per capita of any city in America. Thereby, water treatment was not only needed, it was necessary.

photograph by Kristi Foster Photography

photograph by Captured N Time

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Kait Mauro

photograph by Dan Henrichs Photography

photograph by Ann Aurbach

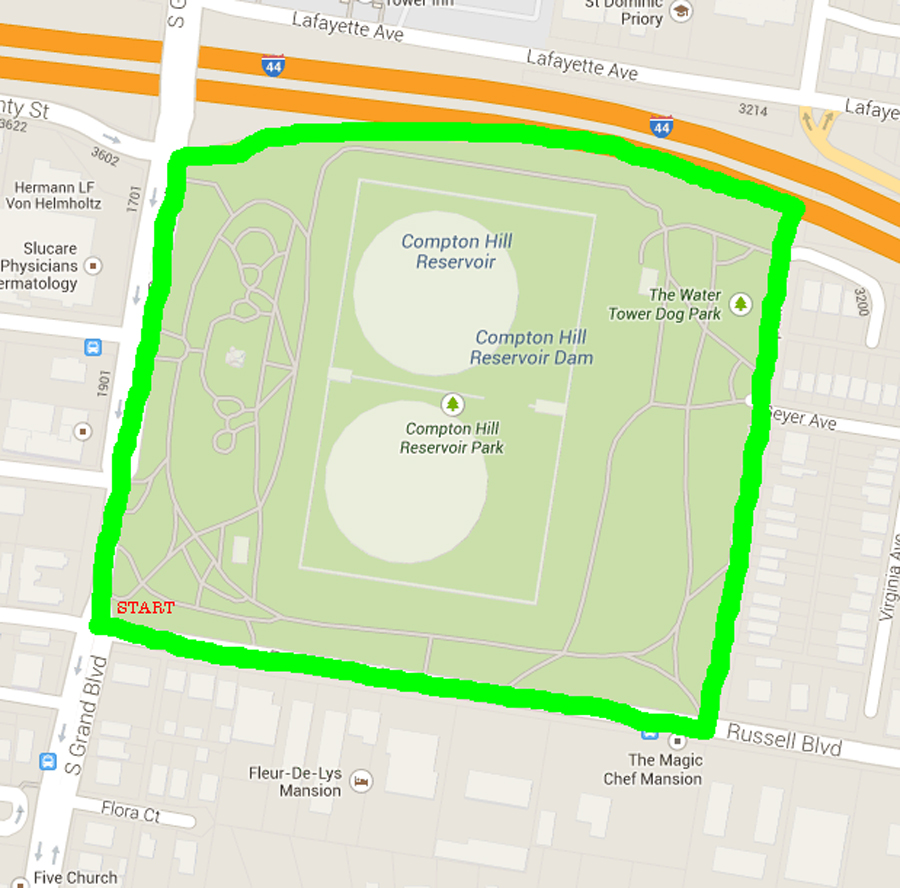

After a laborious few decades of discovery and invention, that included draining the vapid cesspools of sludge downtown (which served both as a source of water and a repository for waste) and designing industrial treatment mechanisms, St. Louis built its first permanent, water treatment plant in 1871. The Bissells Point Plant was designed by James Kirkwood, and included storage reservoirs at Compton Hill. Because it was steam-powered, the Plant could pump water over vast distances, but this also meant that the flow was prone to surges and that water pressure was lesser at upper floors in multiple-story buildings (one of the reasons why most St. Louis kitchens of the era were built either at or below ground level). In order to alleviate the problem, huge standpipes were installed throughout the city that sent columns of pressurized water high into the air in order to regulate water flow throughout the system. In true Victorian fashion, ornate methods were used to conceal the standpipes, and the three which remain standing today are among the most attractive and distinctive structures in St. Louis (in all of the United States, there are only seven extant water towers of this design).

photograph by Jeni Kulka

photograph by Ann Aurbach

photograph by Amanda Miller

photograph by Jocelyn Clemens

photograph by Dan Henrichs Photography, St. Louis

In 1898, the city’s tallest standpipe (at over 100 feet) was encased by an awe-inspiring Romanesque style tower made of limestone and terra cotta. The Compton Hill Tower, as it came to be known, stood alongside the massive water reservoirs, that had served the Bissells Point Plant and still stored much of the drinking water for South St. Louis. Unlike most standpipes of its era, the Tower also featured an enclosed spiraling staircase that led upward to a dramatic viewing platform offering a 360-degree perspective over the surrounding city. There is little doubt that this was St. Louis’ Arch, before the Arch. During the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, the Compton Hill Tower was a major draw, despite being almost five miles away from the center of the Fair (quite a distance by carriage or street car).

<a href=" “>photograph by Theresa Harter

“>photograph by Theresa Harter

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Amanda Miller

photograph by James Palmour

Today, the Tower presides over a charming park that is currently being revitalized by a team of dedicated volunteers according to its original design. On our visit, the St. Louis Water Division and the Water Tower and Park Preservation Society opened the Tower to visitors ($5 admission) in a special event coinciding with the astrological occurrence of the “super moon”. Food trucks, musicians and other vendors were on site for the occasion, which drew many revelers to what was a truly perfect, summer’s night out in St. Louis.

photograph by Jason Gray

photograph by Michelle Williams

photograph by Jeni Kulka

photograph by Mandi Gray