photo by Mark McKeown

Site of the original French Colonial fort and later occupied by the British, Fort de Chartres is today a faithful recreation of what European life in the Mississippi Valley was really like.

photo by Sue Rakers

photo by Jane DiCampo

photo by Mike Matney

photo by Jason Gray

French explorers and missionaries were likely the first Europeans in Illinois, and the first ones to pass through the St. Louis region (when Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet did just that in 1673). Following this initial contact, French settlers established outposts between the Great Lakes and the Lower Mississippi, which cemented an important trade network for the French territorial government in Canada. Among those outposts, were Cahokia in 1699 (the oldest permanent French settlement along the Mississippi River) and Kaskaskia in 1703 (later served as the first capital of Illinois). It’s important to note that both locations were occupied by Native Americans for millennia.

As both outposts prospered and the region’s significance became more clear, the French decided to create a fort to act as the seat of government for its presence in Illinois. The original Fort de Chartres was established in 1719 (the location of the Fort moved east several times during its existence, following flooding and/or changes in the course of the Mississippi River). The original fort was made of wood and construction was financed by the Company of the Mississippi (owned by John Law, who had previously been awarded a trade monopoly by the French government).

photo by Mauren Minich

photo by Dennis Daugherty

photo by Mark McKeown

photo by Sue Rakers

In 1756, the Seven Years’ War (also known as the French and Indian War) broke out, which was a skirmish between the Imperial powers of France and Britain fought upon their colonial territories in the New World, and Fort de Chartres was rebuilt from limestone in anticipation of battle. In 1763, following the defeat of the French military in Ontario, the Treaty of Paris was signed, turning over much of France’s vast territory in North America to Britain. This transition of power, encouraged many French settlers in Southern Illinois to move to safe havens in Missouri (like St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve) or southward to New Orleans. The financial impact of the Seven Years’ War on Britain was significant, and so the British Empire turned to its colonies in North America, both new and old, to contribute to paying down its debt. The new taxes imposed by the British upon the American colonies proved too much to bear, and led to the American Revolution in 1775.

Fort de Chartres was occupied by the British for only a short time, and thereafter, was abandoned and left to the dual actions of time and nature’s power to reclaim.

photo by Maureen Minich

photo by Jason Gray

photo by Joe Rakers

photo by Jane DiCampo

In 1913, the State of Illinois acquired the site of the former Fort de Chartres which by then included only the foundations of structures (concealed under layers of vegetation) and one extant building, the Fort’s powder magazine (considered now among the oldest, surviving buildings in Illinois). With assistance provided by the Federal Works Progress Administration, the State restored the powder magazine, which had been badly deteriorated, and rebuilt the gateway and several stone buildings upon their original foundations. Over time, additional structures were added, and in 1989, the imposing fort walls were added–a sight that, in this location in the 1750’s, as today, inspired awe.

photo by Dennis Daugherty

photo by Mark McKeown

photo by Maureen Minich

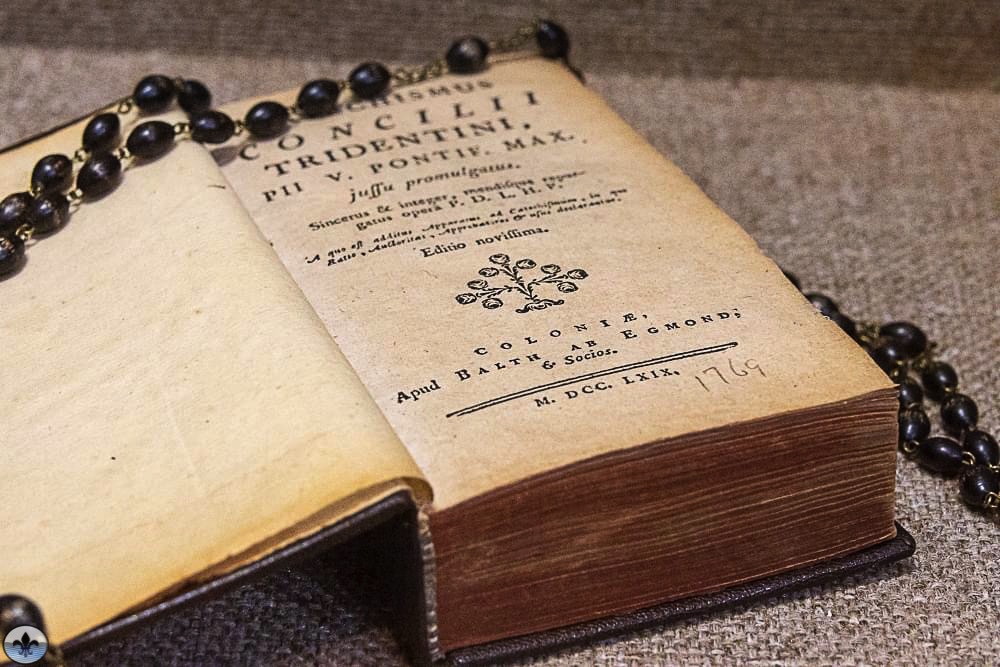

Today, the Fort de Chartres State Historic Site hosts a Museum dedicated to the history of the location, a self-guided tour through tableaux devoted to life at the Fort in the mid-1750s, and a small gift shop with local wares. On our visit, we met a wonderful representative of the Fort de Chartres Heritage Garden Project whose enthusiasm for heirloom plants and vegetables was infectious (as part of its mission, the Project distributes seed packets so that visitors to the site can grow their own historical varieties of vegetables, flowers and herbs). Though it is a bit of a drive from St. Louis (about an hour away, through the rolling bluffs or across the flat expanse of the American Bottom), it is a journey that is well worth a visit.

photo by Mike Matney

photo by Jason Gray

photo by Mike Matney

photo by Sue Rakers